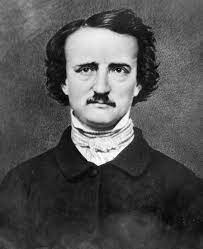

How Edgar Allan Poe came to be adored by those who hated and misunderstood him

How one of the most renowned authors, Edgar Allen Poe, went from being despised and misunderstood to later being loved by millions.

On January 19, 2023, Edgar Allan Poe would have turned 214 years old. He is still one of the most well-known and loved authors in the world.

His face is featured on tote bags, coffee mugs, T-shirts, and lunch boxes. He has sunken eyes, a huge forehead, and untidy black hair. He frequently appears in memes, either dressed as Edgar Allan “Bro” with a popped collar and aviator sunglasses or parodying “Bohemian Rhapsody” by mumbling, “I’m just Poe kid, nobody loves me,” with a raven perched on his shoulder singing, “He’s just a Poe boy from a Poe family.”

Poe appears as a West Point cadet, in the mystery-thriller, The Pale Blue Eye, which Netflix recently released. Poe attended West Point for less than a year before being court-martialed. The Fall of the House of Usher, a Poe-inspired miniseries on Netflix, is slated for release sometime in 2023.

However, in my capacity as a Poe scholar, I occasionally question whether Poe’s appeal is more related to the notion of Poe than it is to the strength and intricacy of his work.

Poe’s most well-known literary characters frequently feature cold-blooded antagonists, after all. In “The Black Cat” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” psychopaths commit seemingly senseless murders; in “Ligeia” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” protagonists mistreat women; and in “The Cask of Amontillado” and “Hop-Frog,” villains wreak brutal, tragic retribution on innocent victims.

In depraved short stories, Poe urges readers to adopt viewpoints that don’t quite fit with the current cultural context, which is marked by safe spaces, and trigger warnings.

At the same time, the idea of Poe as a writer seems to draw on a popular love of outcasts, rebels, and underdogs who ultimately succeed.

Poe’s death in 1849, which was announced cruelly in the New-York Tribune, gave rise to the notion of Poe as the underdog. The paper bitterly stated, “This revelation will startle many, but few will be mourned by it.”

Poe’s occasional friend and ongoing opponent Rufus W. Griswold, who wrote the obituary, asserted that the deceased had “few or no friends,” and then launched into a sweeping character assassination of Poe based on exaggerations and half-truths.

Oddly enough, Griswold served as Poe’s literary executor and enlarged the obituary into a biography that was included with the author’s collected works. If it was a marketing gimmick, it was successful. Poe’s alleged lack of friends was disproved by them, and for decades, the media debated the man’s true identity.

Poe was ready to be accepted as the enduring underdog at the turn of the 20th century. Around this time, Poe did frequently appear on stage as the subject of a number of biographical melodramas that portrayed him as a sad figure whose lack of success was more a result of an unfriendly cultural and publishing scene than it was due to his own shortcomings.

Poe was rarely well paid during his lifetime, and the majority of readers first saw his writing through magazines. However, Griswold’s edition went through 19 printings in the 15 years following Poe’s passing, and ever since then, his stories and poems have been translated and endlessly republished.

Poe’s slanderous portrayal by Griswold and the dark themes in his stories and poems continue to color readers’ perceptions of him. The prolonged reaction or counterimage of Poe as a tragic hero, a tortured, misunderstood artist who was too good, or at least too cool, for his world has also been developed.